There’s a particular point I’ve been trying to articulate about HomePod vs Amazon Echo and all the others that I haven’t quite figured out how to express succinctly in a tweet. So I’m going to resort to charts.

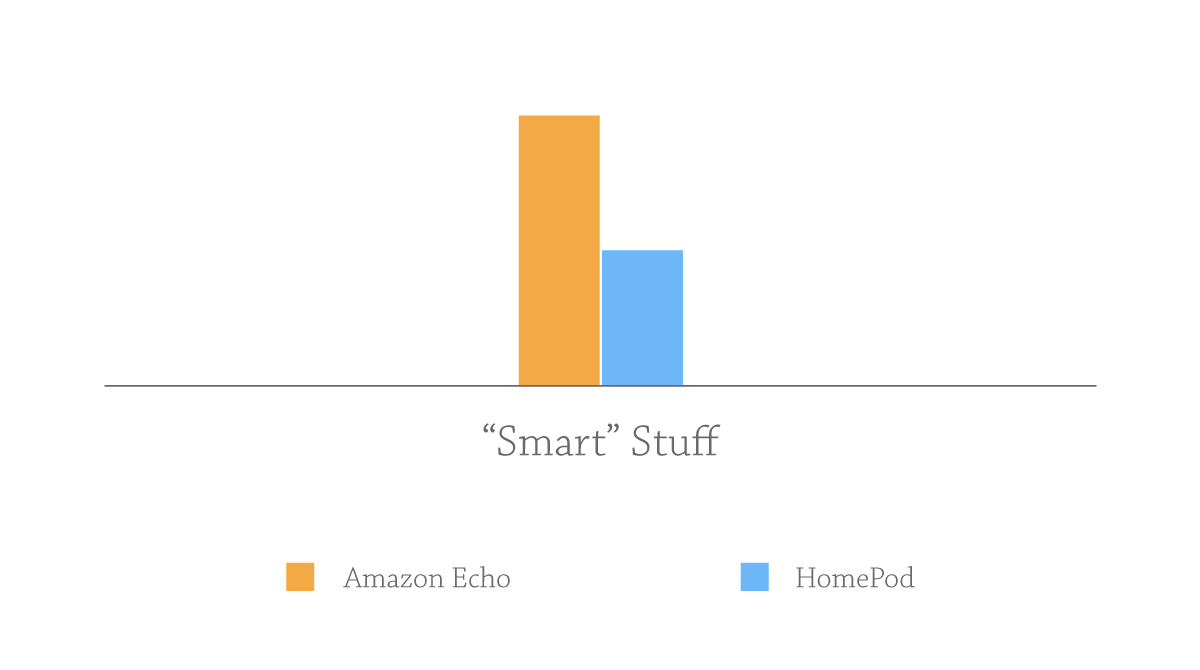

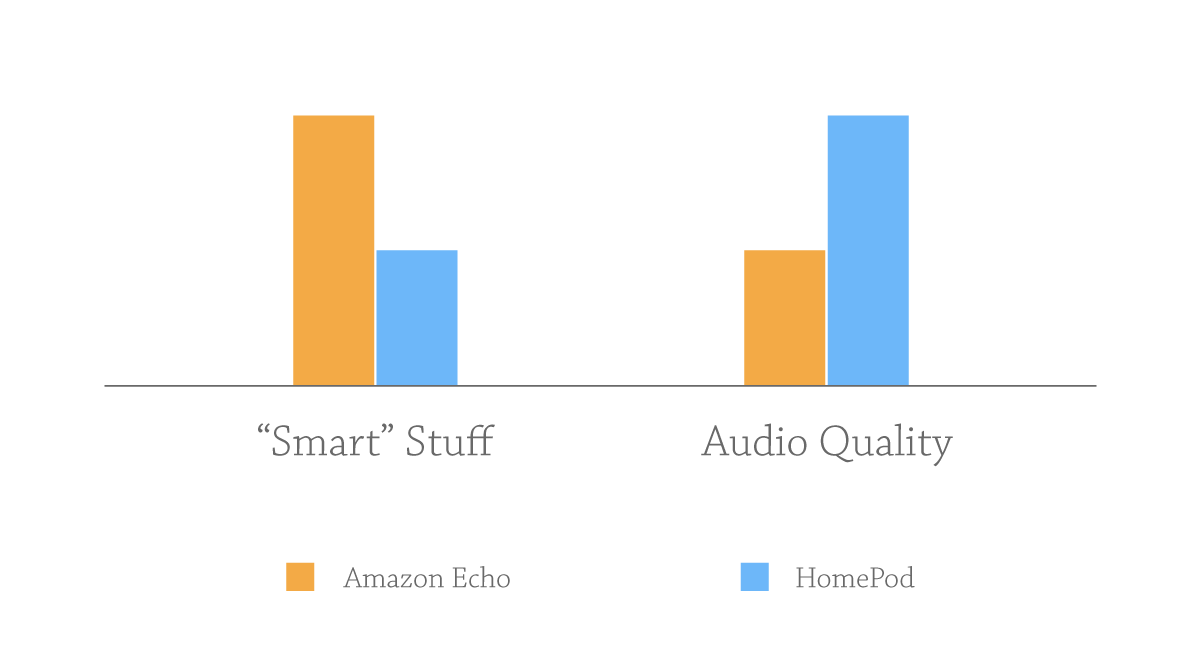

If we wanted to compare HomePod and Echo as “Smart” devices, digital assistants—whatever term you want to use—I think most people will agree that Echo has an advantage. How much of an advantage is up for debate, but let’s be extremely generous to the Amazon fans and say that Echo is twice as good as HomePod in this area.[1] That sounds like a big deal, right? Echo is soooo much better at being a voice assistant. Twice as good! Apple should be quaking in its boots.

But better is a relative term. You can be better and still not be good, right?

Let’s switch gears for a moment and compare the two devices as speakers. Here we get a different chart. Personal differences in taste aside, only a complete lunatic would say that HomePod isn’t significantly better than Echo at being a speaker. But again, how much better is up for debate. I don’t think it’s totally unreasonable to say that HomePod is twice as good as Echo at sound, though. [2]

So we’ll add that to our chart.

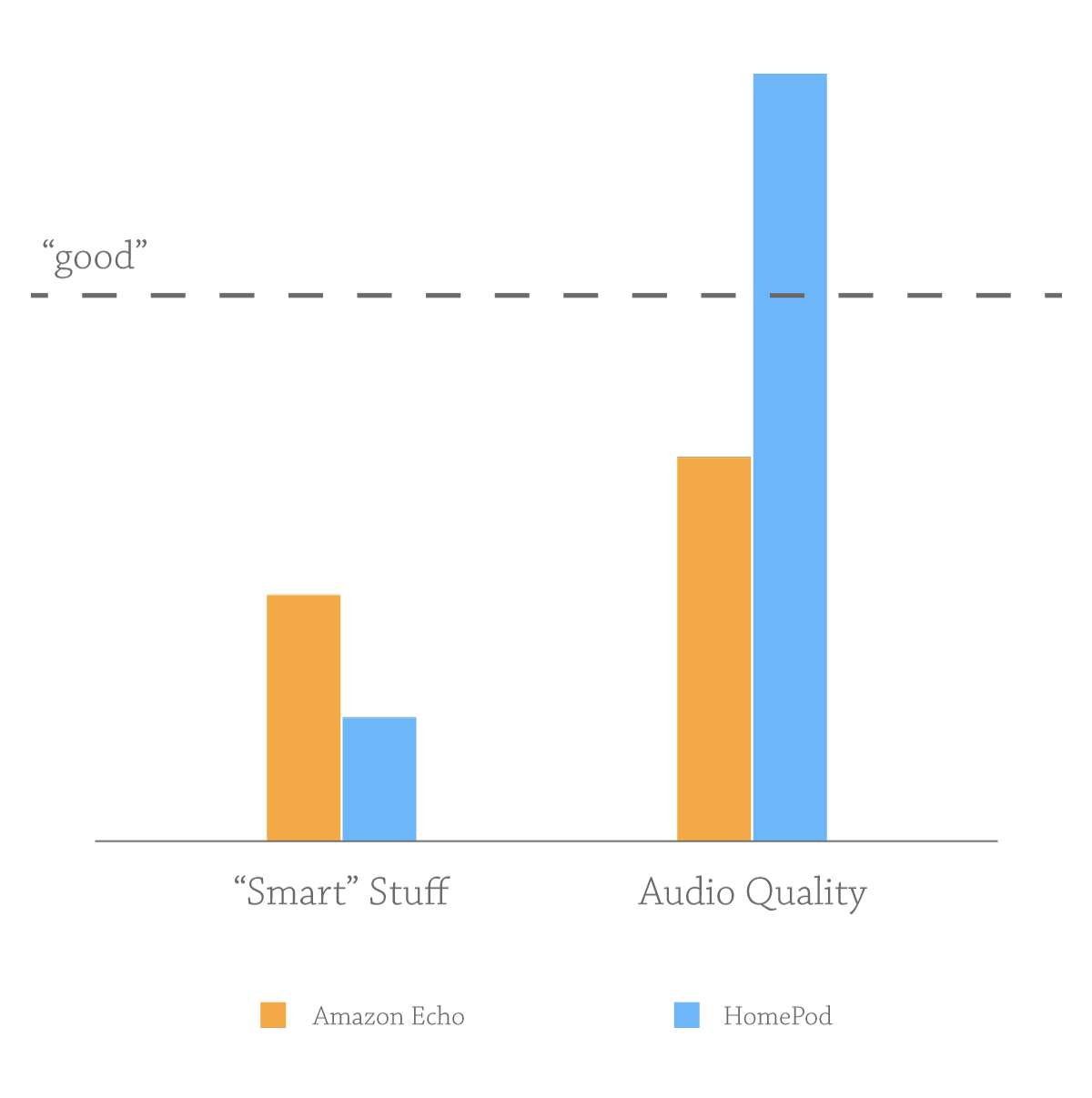

But we have the same problem again. We know one is better than the other, but we don’t have a sense of where “good” falls.

Without knowing where “good” is, anyone can wave either one of these comparisons away and chalk it up to priorities. Some people care more about the sound quality. Some people care more about the smart stuff. Sounds like a toss-up, right?

But there’s a threshold of quality where people consider something “good.” Where the general public—not just a niche of enthusiasts—agrees that a technology has gotten significantly good enough to make it ready for prime time.[3]

We reached the “good” threshold for speakers decades ago. The subcategory of affordable bookshelf speakers got there sometime in the past few years.

But we’re nowhere near “good” yet when it comes to digital assistants.

I say this with no small amount of respect for how hard this technology is and how far it has come recently. I’m as excited as the next geek when it comes to the future of AI and voice recognition. I think it’s all super cool.[4]

But it’s not good. Not for most people. It’s barely past the point of being a parlor trick, if we’re being honest. Answering trivia questions? Turning on the lights? There’s a reason even early adopters generally resort to using these devices for a small set of simple tasks. That’s about all they can do reliably.

I firmly believe we’ll get much better voice assistants eventually, but the fact of the matter is “good” is a long way off.

This is the reality of our chart.

There are a few things that have to happen before voice assistants are going to stop being the butt of an SNL skit. First and foremost, they need to learn when we’re actually talking to them.

Listen to any tech podcast hosted by a voice assistant fan (there are lots of them) and wait for hilarity to ensue as they say the word “Alexa” or “Siri” in conversation (or any word that sounds remotely like those trigger words), and their Echo or iPhone proceeds to respond as if a request were being made. This is followed by five seconds of “Alexa STOP!!!” And laughter from the co-host.[5] Never mind the complaints that come later from listeners as all of their Echos and iPhones go off.

This happens so often that many hosts have resorted to substitute expressions. (Hey, Dingus!) It’s a running joke, even amongst the most enthusiastic of early adopters.

Have you ever noticed this never happens to Chief O’Brien on Star Trek? He can say “Computer, how long before the Dominion ship is within weapons range?” And he gets the appropriate response. But then he says “Captain, I’m going to need to tap into their central computer.” And the computer does nothing.

That’s because science fiction authors, unlike Alexa fans, understand that sensible people would not depend on voice control until this basic requirement was met.

Siri, Alexa—whatever name Google Home responds to[6]—need to be that smart. Non-geek humans are going to laugh you out of the room in the meantime. The device can’t be simply listening for “magic” words. It needs to know when it is being spoken to and more importantly, when it is not. Human beings are very good at this, and we expect the same level of skill from anything we talk to.[7] This is not an easy thing to get out of a computer, clearly. Because it hasn’t happened yet, and people have been working on it for decades. But until we resolve this, digital assistants are annoying more often than they are useful.

And that brings me to the next key word in this discussion—usefulness.

Here’s what I really want out of a virtual assistant: Assistance. Not trivia questions. Not timers. Utility. It needs to actually make my life significantly easier.[8]

Let me give you an example. And there’s no doubt in my mind this will be possible someday.

“Alexa, book me a flight for Peers Conf.”

If I had a human personal assistant, that’s all I’d need to say to get this task done. They would go straight to work, and I’d get on with my day. But in order for Alexa to do this, all of the following would need to be in place:

- Alexa would need to be able to search the web and figure out that Peers Conf is a conference happening in April in Austin, TX. Not just to report that back to me, but to understand that this is the reason for my trip.

- She would need to figure out the dates for the conference, then take into account my usual preference to arrive a day early, and if the conference ends near a weekend, to stay through until Sunday evening.

- She would need to know my preferred flight times, the airlines where I have frequent flier accounts, that I fly nonstop whenever possible, that I’m starting in New York, but I hate Newark airport, and that I prefer an aisle seat.

- If she had any conflicts between any of my preferences, she’d have to follow up: “There’s no available flight after 6:30am on Sunday morning. Do you want to extend the trip to Monday or take that early flight?” (Also, if I’ve moved on and started watching TV or listening to music, or I’m just talking to another person in the room, she would need to be courteous and not interrupt me. Perhaps she would send me a quick text or push notification and wait for my response.)

- After settling all of this, she’d have to compile a summary and send it to me in an email or push notification to my phone so I could confirm. Once confirmed, she’d have to be able to book everything automatically with the correct credit card and send me the receipts via email and place the appropriate pass into my electronic wallet.

That is a digital assistant. And any device that could accomplish this reliably would be as popular as smart phones are today.

Wake me up when Alexa can do anything remotely this complex, and I’ll start to worry about Apple “falling behind” in this space.

Because here’s the thing: that level of complexity is not just a matter of gathering more data and training our AI models a little longer. It’s not a matter of third party apps. It’s not a matter of open vs. closed. It’s not a linear progression from where we are today to that. It’s going to take some major breakthroughs, deep connections into my life—financial, personal, and historical—that require user trust. (Amazon is never going to put this together by looking at my paper towel order history.) Not to mention the agreements between companies in several different industries required to have a digital assistant make purchases on my behalf. Heck, Amazon doesn’t really have a strong motivation to make something like this happen, because it would stand to gain nothing from the transaction.[9]

So yes, other platforms may currently be “better” than Siri. But when none of the platforms is good, what difference does that make, except to a small niche of enthusiasts? By all means, enjoy the Echo if you want to live on the bleeding edge of voice assistants. But don’t try to convince me Apple is doomed in this space, or that I’m missing out big because I prefer to listen to a good speaker and set my timers with Siri.[10]

That’s why even though it’s too early in the race to tell who will come out ahead—and there’s no reason one winner needs to take all in this field, by the way—I wouldn't count Apple out in the long term for digital assistants. At least Apple knows the difference between a tech demo and an actual product. More critically, it knows to prioritize features where it can actually deliver something good, rather than something better at bad.

In my limited experience with Alexa, mostly watching others struggle to get her to understand anything, I’d put it more like 10% better. But I don’t need Siri to be even close to make my point here, so I’ll concede this much. ↩︎

You can fart music that sounds better than Echo, as far as I’m concerned. So I’d put this more at HomePod being 10 times better than Echo, easy. But again, I don’t need to prove that to make my point, so I’ll be generous to the opposing side once again. ↩︎

There was a time when only enthusiasts thought personal computers were worth a damn. The general public thought they were expensive and not useful for much. And you know what? The general public was right. Enthusiasts eventually made computers that were good enough for the rest of humanity, but that took a while. ↩︎

I’m old enough to remember “My voice is my password” on my Mac running System 7. Ask your grandpa about those good old days of voice recognition technology. ↩︎

ProTip for podcasters: Turn off your Echo or HomePod before recording. See also, Do Not Disturb mode on your iPhone and Mac. Pretty basic stuff. ↩︎

It’s telling I don’t even know the answer to this. Google, who by all rights should be miles ahead of both Apple and Amazon on this front, has done such a poor job of marketing their assistant that even a geek like me doesn’t know what to call it. ↩︎

Heck, even my cat is pretty good at knowing the difference. ↩︎

I'm aware that for some, just having the option to use voice, unreliable as it may be, does make their lives significantly easier. I'm talking about reaching a critical mass where the majority of people on earth get real utility from voice-activated devices. ↩︎

The Echo is a loss leader designed to get you to buy more stuff on Amazon. Jeff Bezos doesn’t want to help you buy airline tickets. HomePod, on the other hand, is a high-margin piece of hardware that makes money directly, at least. ↩︎

Multiple timers, Apple. Please. No excuse for that one. ↩︎